HMS

Tweed (K250) – Hatfield's forgotten warship

HMS

Tweed (K250) – Hatfield's forgotten warship

You wouldn't normally associate a landlocked Hertfordshire town with a Royal Navy warship. However, when such an association did exist, you wouldn't think it would be forgotten – especially not after 83 men made the supreme sacrifice for their country. Sadly, it has – and, at the time of writing, not one of the Hatfield inhabitants questioned in an unofficial straw poll had heard of HMS Tweed (and some had lived here for fifty years). Although, to be fair, HMS Tweed is mentioned in Brian G Lawrence's book, Hatfield at War.

The HMS Tweed in question was a World War II, River class frigate – the seventh Royal Navy vessel to bear that name (the first was launched in 1759).

HMS Tweed datafile

Manufacturer: Scottish shipbuilder A & J Inglis (who also made her sister ships Halladale, Helmsdale, Kale and Meon).

Build time: 22 months, 17 days

Launched: 24 November 1942

Commissioned: 28 April 1943

Pennant number: K250

Captain: Lieutenant-Commander Robert Stevenson Miller

Dimensions*: 301.5 x 36.67 x 12ft

Armament*: 2 x 4-inch guns; 2 x 2-pounder guns; 2 Oerlikon anti-aircraft guns, 1 x hedgehog (anti-submarine rocket thrower) and 10 x depth charge launchers (primary armament for anti-submarine vessels).

Crew: 139 on her final voyage (140 was usual for a ship of this class).

Displacement*: 1,370 tons (by comparison the cruiser HMS Belfast displaced 10,000 tons)

Sunk: 7 January 1944 – torpedoed by U305 commandered by Kapitanleutnant Rudolph Bahr

*Based on overall River-class specifications for vessels built 1940-42. HMS Tweed's displacement may have varied due to having a different propulsion system. Also, there were variations in armament due to a shortage of weapons.

River Class Frigates

River class frigates were designed early on in the war as replacements for Flower class corvettes (frigates and corvettes in WW2 were usually larger ships than sloops but smaller than destroyers).

Specifically designed as anti-submarine vessels, River class frigates also afforded a measure of anti-aircraft protection as convoy escorts but were not equipped to take on German surface vessels (this was largely left to the Home Fleet and aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm – aided by British submarines and the aircraft of the RAF).

River class frigates served with distinction during some of the bleakest days of the Battle of the Atlantic when German submarines, called u-boats, organised into groups known as wolfpacks, wreaked havoc among merchant shipping.

River class frigates were later replaced by the Loch and Bay class frigates before the end of the war but they continued in service. They are credited with sinking 10 German u-boats, and damaged many more.

As their main role was to deter attacks on largely unarmed merchant ships carrying essential war material (like munitions, tanks and guns), the number of lives they saved cannot be easily quantified. Nor is it possible to say how many times the outcome of a battle changed because those valuable cargoes safely reached their destination.

River class frigates were used in WWII by the Royal Navy, Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). Nicholas Monserrat, author of the acclaimed book The Cruel Sea served on River class frigates. He also recounted his experiences in HM Frigate, and the fictional novel Three Corvettes.

Hatfield's Warship Week 1942

During WWII there were a number of National Savings campaigns run in Britain. In a healthy atmosphere of patriotism and civic-mindedness, towns and villages competed with their neighbours to raise money for the armed forces. Fetes, village fairs, concerts, dinner dances and other activities were organised locally as part of the fundraising effort. National campaigns were run every year, usually lasting a week, and had a theme – which would be adopted locally and financial targets set.

The 1942 National Savings campaign theme was Warship Week.

Hatfield & District planned to raise £120,000 to provide the Royal Navy with a fully equipped corvette. Hatfield's Warship Week ran from 7-14 March 1942 (while part of a national campaign, there was some flexibility to decide locally which week it would be held in).

In the end, Hatfield & District raised over £150,000, which was considered to be enough to pay for one of the Royal Navy's new convoy escort vessels – HMS Tweed, a River class frigate.

Strictly speaking, River class frigates were originally designated as twin-screw (two propellors) corvettes. Frigates had not been part of the Royal Navy fleet for decades, if not centuries. However, thanks to some 'unauthorised' action by the Royal Canadian Navy, the British Admiralty was forced to change its classification and frigates rejoined the fleet.

A formal 'adoption' ceremony was held in Hatfield in May 1943, the Royal Navy was represented by Admiral Sir Percy Royds. Initial research suggested that the ceremony was held at St Audrey's School (before it was destroyed by a V-1 in 1944). Photographs at the Mill Green Museum show that the ceremony took place in the playground in front of the Countess Anne Science School building, which is still standing (it seems both schools were sharing the site). Also present at the ceremony was Lord Plumer and Councillor E C Doust-Smith. An exchange of plaques took place. The rectangular Hatfield plaque bearing the district's coat of arms, mounted on a block of Oak from Hatfield Park, was later installed on HMS Tweed and went down with the ship. Rather shamefully, no one appears to know what happened to the larger shield – with the Royal Navy crest bearing an anchor with a rope wrapped around it – that was given to Hatfield. Enquiries at the Hatfield Town Council, Welwyn Hatfield Borough Council, Mill Green Museum, Hertfordshire Archives & Library Service, British Legion of South Hatfield (established after the war), and the Royal Naval Association Club in Welwyn Garden City, failed to shed any light on its whereabouts.

Documents at the Hertfordshire Archives & Library Service show that there was an exchange of Christmas greetings between the town authorities and the Captain of HMS Tweed later that year. There was also an exchange of letters after the sinking.

Later National Savings campaigns:

- 1943 Wings for Victory

- 1944 Salute the Soldier

HMS Tweed's claims to fame

One of only six River-class frigates (out of over 130 built) to be equipped with turbine engines. The others being: Cam, Chelmer, Ettrick, Halladale and Helmsdale.

Part of the escort group that sank the U-536, on 20 November 1943, while it was on Operation Kiebitz – a rescue mission to free German u-boat aces held in Canada (HMS Tweed while not directly involved in the sinking did pick up survivors).

One of only six River-class frigates to be lost due to enemy action. Itchen and Mourne were also sunk. Three others – Cam, Lagan and Teme – were scrapped due to heavy damage.

7 January 1944 was the date the Germans abandoned their wolfpack and patrol line tactics in the face of growing Allied seapower, which makes HMS Tweed possibly the first warship to be sunk after what was effectively a German acknowledgement of impending defeat.

Please note: more information on Operation Kiebitz can be found on the Quebec Naval Museum web site:

http://www.mnq-nmq.org/english/vivez/impacts/operation.htm [07.10.09 – site seems to have been suspended but there are some details on Wikipedia]

Information on HMS Tweed's wartime operations can be found on the detailed naval-history.com web site:

http://www.naval-history.net/xGM-Chrono-15Fr-River-Tweed.htm

[7 November 2009 – HMS Tweed may have another claim to fame. Please click here for more details...]

The Sinking

HMS Tweed was torpedoed by the German submarine U305 commandered by Kapitanleutnant Rudolph Bahr on 7 January 1944.

On that fateful day, with a four-engined aircraft overhead (Liberator or Flying Fortress – accounts differ), HMS Tweed was the port wing ship in a line abreast formation with two other vessels in her escort group – HMS Nene and a Canadian naval vessel HMCS Wasekiu – steaming at 13 knots. An Asdic contact was picked up by HMS Tweed but it was not initially identified as a submarine (the ship's captain Lt Cmdr Stevenson Miller's initial report said that they had had numerous contacts from whales and other marine life in the preceding 24 hours). Precious time was lost before it was established that it was a submarine contact. By then it was too late for HMS Tweed and most of her crew.

At 16:13 hours a torpedo detonated near the 'Y' gun turret, breaking the ship in two and sending up a plume of water and debris some 200ft into the air. The engine room bulkhead gave way, half a depth charge landed on the bridge, and the quarterdeck floated away.

The remainder of the ship immediately started to list heavily to the starboard (right), and the bows came out of the water till the ship was nearly vertical before she sank at 16:15 – two minutes after being struck.

Although it was daylight with good visibility, a calm sea and relatively warm water temperature the death toll was horrendous.

Many of the survivors in the water were killed when at least one of her depth charges exploded as she sank. Virtually all the other survivors were injured. For many, the mental and physical injuries would stay with them for the rest of their lives.

A number of other survivors lost their lives when an overcrowded Carley float capsized.

Due to the threat posed by the German submarine, the other escorts and merchantmen in the convoy could not stop or aid the survivors straight away. Some survivors drowned trying to swim towards other ships, not understanding why they were not being rescued and fearing being abandoned (Unbelievably, even though this was in 1944, the Royal Navy apparently did not instruct sailors on what to do if their ship sank – it seems that they thought anything suggesting such a notion would have a bad effect on morale).

It was nearly an hour after the sinking before HMS Nene dropped Carley floats and launched a whaler to start rescue operations (some would be in the water for 2.5-3 hours). For many it was too little, too late. A few died from their wounds, at least one was recovered already dead (one injured survivor died from his wounds on 27 January 1944). They were all buried at sea the next day. The others were never seen or heard of again.

The Aftermath

As the sinking took place in daylight with good visibility, a calm sea and with a relatively warm water temperature, the high death toll shocked the Admiralty, which ordered a Board of Inquiry. It was held on 13 January 1944 at HMS Ferret (a shore station) at Ebrington Barracks. President of the Board of Inquiry was Commander A M McKillop of HMS Hotspur. The Board of Inquiry report, including witness statements and findings, along with some of the original messages sent and received during the action are preserved in the National Archives at Kew.

While the lack of training for dealing with having your ship sunk from under you was highlighted, it appears relatively little was done afterwards.

The Board of Inquiry formed the opinion that HMS Tweed was sunk by a non-contact torpedo and not a GNAT (German Navy Accoustic Torpedo) largely based on where it hit the ship. However, German post-war accounts usually state that HMS Tweed was sunk by the U-305 using a GNAT.

Kapitanleutnant Rudolph Bahr and the crew of the U-305 cannot shed any light on the matter as they never returned to base.

U-305, which sank HMCS St Croix on a previous patrol, was thought to have been sunk on 17 January 1944 by the destroyer HMS Wanderer and the frigate HMS Glenarm. However, post-war research suggests that the U-305 and all 51 crew may have been lost a day earlier due to one of her own torpedoes malfunctioning (it's possible that the difference in 'normal' behaviour that led the British Board of Inquiry to conclude that it was a non-contact torpedo, and not a GNAT, that sank HMS Tweed was an early indication that the torpedoes were becoming defective).

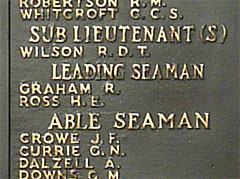

A key fact to come out of the inquiry was the heroism of Leading Seaman Henry Edward Ross, 23, Official Number SD/X.1223, who stood at the bottom of the forward alleyway of the doomed ship directing ratings up the ladder and by doing so probably helped save the lives of a number of more inexperienced ratings. He did not survive. He is commemorated on the Royal Navy memorial in Portsmouth on the panel for members of the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, as shown in the photo below. Although the lack of any medal listing against his name suggests that his heroism and sacrifice did not receive official recognition.

Please note: if you are looking for the name of a friend or relation on the Royal Navy memorial, names are listed individually by year, branch of the Royal Navy, rank and then alphabetically. WWII casualties are listed on a terrace below the main memorial on the landward side (as shown in the photos used for HMS Tweed's Roll of Honour, link below).

Forgotten warship

Sadly, HMS Tweed appears to have been lost in more ways than one.

During the course of compiling the information on the vessel for this site, enquiries about the possibility of getting a photograph of HMS Tweed were made at the Imperial War Museum, Royal Naval Museum and the National Maritime Museum. While everyone contacted was more than willing to help, it emerged that none of these major national collections had a photo of the ill-fated K250. However, the enquiries did lead to information that the papers of HMS Tweed's makers, A&J Inglis, had been deposited with the Mitchell Library in Glasgow. Unfortunately, raised hopes of a manufacturer's photo were soon dashed.

An exhaustive search for information (600+ Google entries) did lead to the surprising discovery that there was a sizeable relic of HMS Tweed – in Canada. The Crow's Nest Officers' Club in Newfoundland, Canada, possessed a gunshield bearing the crest of HMS Tweed (shown in the photo at the top of this page). The Canadians proved to be stout comrades decades after the war's end. Not only did they provide what information they had, the Club's secretary, Lieut Cmdr (Retd) Margaret Morris, also very generously allowed an appeal for information to be published in their newsletter.

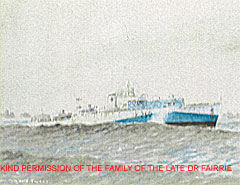

This led to contact being established with the families of two of the surviving officers from the sinking (but sadly now deceased) – the late Lieutenant Michael Angus Wilson and the ship's surgeon the late Surgeon Lieutenant Dr Tony Fairrie. Speaking to the families, it became clear that the survivors may have escaped with their lives but they did not escape unharmed. In particular, apart from injuries that were to trouble him for the rest of his life, Dr Fairrie also had to deal with the memory of those hours in the water watching the men he had spent the previous months and years caring for die one by one, helpless to do anything for them.

Years later, Dr Fairrie paid for ads in his local newspaper on the anniversary of the sinking to commemorate his lost shipmates, and their sacrifice in the cause of freedom. Below is a photo of the picture of HMS Tweed that hung in his study. At the time of writing, it remains the only known picture of HMS Tweed (K250).

An idea of what HMS Tweed would have looked like can also be had from the 3 inch diecast model of a River class frigate shown below. This model may be one of those produced by H A Framburg & Co, Chicago. Their main line of business was producing lighting fixtures but during WWII they produced a range of models for training US Forces. Ship models tended to be either 5 inch or 3 inch – the larger size being used by the instructors. Their purpose was to help military personnel familiarise themselves with ship silhouettes in order to avoid any 'friendly fire' incidents.

The Crow's Nest Officers' Club

The Crow's Nest Officers' Club in St John's, Newfoundland, Canada, was founded in 1942 – the year HMS Tweed was launched.

Especially in the early days, men fighting in the Battle of the Atlantic were at war from the time they boarded their ships (on at least one occasion, after a perilous voyage, a ship berthed, switched off its degaussing equipment – used as a countermeasure against magnetic mines – and promptly blew up as an undetected mine, laid by a submarine or aircraft, detonated). In British ports there was the ever-present danger of German bombers. While virtually everywhere else the menace of enemy submarines lurking outside the harbour entrance was a constant peril.

The freezing cold and Atlantic winter storms were as much of a menace to life and limb as was enemy action. But, regardless of the hazards, men on both sides of the Atlantic answered their country's call to duty. Some were made to pay a terrible price for their bravery.

St John's was a key harbour in WWII – weapons and ammunition produced in Canadian and US factories were sent across North America by train to the town to be shipped across to the battlefields of Europe and further afield. While even more precious human cargoes – US and Canadian troops, and RAF personnel who had completed their training in Empire Flying Training Schools in Canada – were shipped from here. For them it would be a few nerve-racking weeks braving the elements, mines, u-boats of the Kriegsmarine and the aerial assault of the Luftwaffe. For the naval personnel, they had a brief shore leave and then they went out and did all again.

British officers and sailors returned to their homes and families. But while waiting for those homeward voyages, they would have to make do without the comforts of home and family. At least until they returned home – providing they survived the journey.

It was realized that while there were sufficient venues for sailors to relax and unwind in St John's, there were no suitable clubs or messes for officers. Captain E R Mainguy and Mrs Dorothy Outerbridge set about finding a suitable venue in the busy and crowded port. They eventually found a cosy nook in a fourth floor warehouse that could only be reached by climbing a flight of 59 steps (according to one account, the club reputedly got its name after a visitor, exhausted by the ascent, asked "Crikey, what's this, a ruddy crow's nest?").

They created a snug little home-away-from-home where officers could relax after a hazardous voyage or enjoy a few creature comforts before shouldering the burden of command and braving the perils of the Atlantic again.

It soon became an established tradition that officers from ships on their first visit would leave a keepsake of their visit. Usually, these were in the form of a ship's crest on a formal plaque or gunshield. These were mounted on the walls of the club (as shown in the photo below) and would be a sort of welcome home for those making a return visit. Sadly, like in the case of HMS Tweed, they have also become reminders of those who never returned.

HMS Tweed – Roll of Honour

On her final voyage HMS Tweed had a complement of 139 officers and men. Eighty three officers and men (3 officers and 80 other ranks) died after she was torpedoed. The names of the dead are listed on a separate memorial page. The eldest was 47, the six youngest were 18.

Please click here to visit the HMS Tweed memorial page

HMS Tweed – Survivors Roll of Honour

Fifty six officers and men survived the sinking. Nearly all of them were injured. Over 65 years after the event, injuries and the passage of time have taken their toll and few, if any, are still with us today.

Please click here to visit the HMS Tweed Survivors memorial page

Thanks and acknowledgements

Researching the history of HMS Tweed proved more challenging and involved asking more people for assistance than for any other section in this web site.

Special thanks to:

Lieut Cmdr (Retd) Margaret Morris, Secretary of the Crow's Nest Club in St John's, Newfoundland, Canada, who proved to a great help and support.

The widows and families of the late Lieutenant Michael Angus Wilson and the ship's surgeon the late Surgeon Lieutenant Dr Tony Fairrie (in particular, their widows and sons – Ian Wilson and James Fairrie). Dr Fairrie's obituary was published in the British Medical Journal: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/extract/333/7580/1224-b

Lisa L. Piercey, NavSim Technology Inc – for the photos of HMS Tweed's gunshield on wall of the Crows Nest Club.

Gordon Summer of www.naval-history.net for permission to draw on his HMS Tweed's casualty list and link to his site (which has been merged with information from naval records and the CWGC database).

Mat Knight, Navy Search, for providing information on HMS Tweed survivors, and helping resolve conflicting information.

Mrs Jackie Withers, Commonwealth War Graves Commission, for providing information on HMS Tweed survivors, and helping resolve conflicting information.

Others who helped included: Ian Proctor, Imperial War Museum; Mrs M Newman, Royal Naval Museum; Graham Thompson, National Maritime Museum; Elaine MacGillivray, The Mitchell Library; Martin O'Brien, British Legion – South Hatfield; staff at the National Archives, Hertfordshire Archives & Library Service, Royal Naval Association Club – WGC, and the Mill Green Museum.

Brian Lavery's book, River-class Frigates and the Battle of the Atlantic, published by the National Maritime Museum in 2006, was a useful reference source.

Back to: Features on Hatfield23 July 2009

7 November 2009 – additional information added

3 September 2010 – additional information added